Checklist for auditing consistency with the IPCC regarding climate action

- Is climate action an overriding priority, on the basis of e.g. the gross injustice?

- Is a limit to global warming specified, generally 1.5°C?

- Is there adherence to the IPCC CO2 budget?

- Is equity between nations incorporated?

- Are all CO2 emissions included, particularly those embodied in imports and exports and those from aviation and shipping?

- Is the size of appropriate annual emission cuts specified e.g. double digit percentage cuts in developed countries?

- Are any policies discussed consistent with this timescale?

- Are false solutions avoided?

Why is a checklist needed?

While there is little dispute that the climate is changing, or that it is due to human activity, or that climate change needs to be limited, the actions that would limit climate change are not being taken. The implications of the scientific consensus together with manind's stated commitments to human rights are not being translated into action. The logical steps that should convert the scientific consensus into action are not being acted on. This is termed implicatory denial by sociologists - see document 147. There are concerns that climate denial in various forms is near universal across society [1].Messaging that is inconsistent with the scientific consensus has been identified as a barrier that is delaying the radical action needed [2]. In response to this problem, Scientists for Global Responsibility (SGR) has launched its Science Oath for the Climate [3], which commits signatories to

"explain honestly, clearly and without compromise, what scientific evidence tells us about the seriousness of the climate emergency..."

and

"speak out about what is not compatible with the commitments, or is likely to undermine them".

A checklist should help identify where the failures are occurring, and help to correct them. Checklists are used in many situations to ensure adherence to high standards in complex areas. For example, checklists of statistical methods are widely used in medical journals (e.g. The British Medical Journal [4]) to assist the writing of articles and for reviewer's to assess articles that have been submitted for publication.

Elements of a checklist

The following is a suggested checklist.1. Is climate action an overriding priority, on the basis of e.g. the gross injustice?

Climate change is resulting in gross injustice in that the people who are suffering the most from climate change are the ones least responsible for it - see document 91.

2. Is a limit to global warming specified, generally 1.5°C?

Is the aim clearly stated in terms of a limit to the rise in global temperature (generally 1.5°C) - see document 152?

3. Is there adherence to the IPCC CO2 budget? Is the mechanism for limiting global warming clearly stated to be limiting further total global CO2 emissions to the CO2 budget specified by the IPCC?

See document 93.

4. Is equity between nations incorporated? Are the implications of the international commitments to global equity properly taken into account, i.e. that developed nations cut emissions faster than the global average?

The basis for any calculation should be explicitly stated, e.g. as equal per capita shares.

See document 122.

See document 122.

5. Are all CO2 emissions included, particularly those embodied in imports and exports and those from aviation and shipping?

See document 31.

6. Is the size of appropriate annual emission cuts specified e.g. double digit percentage cuts in developed countries?

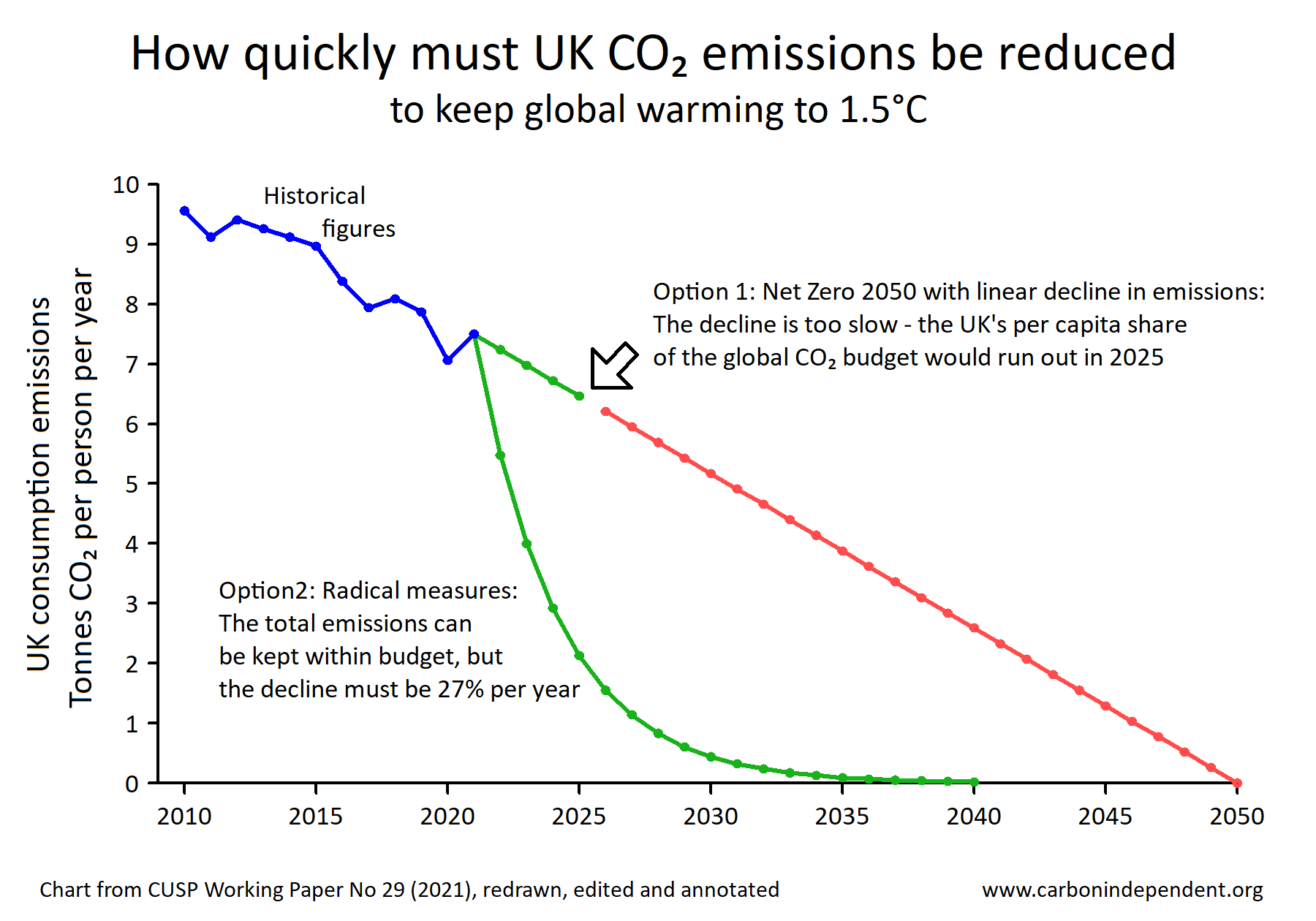

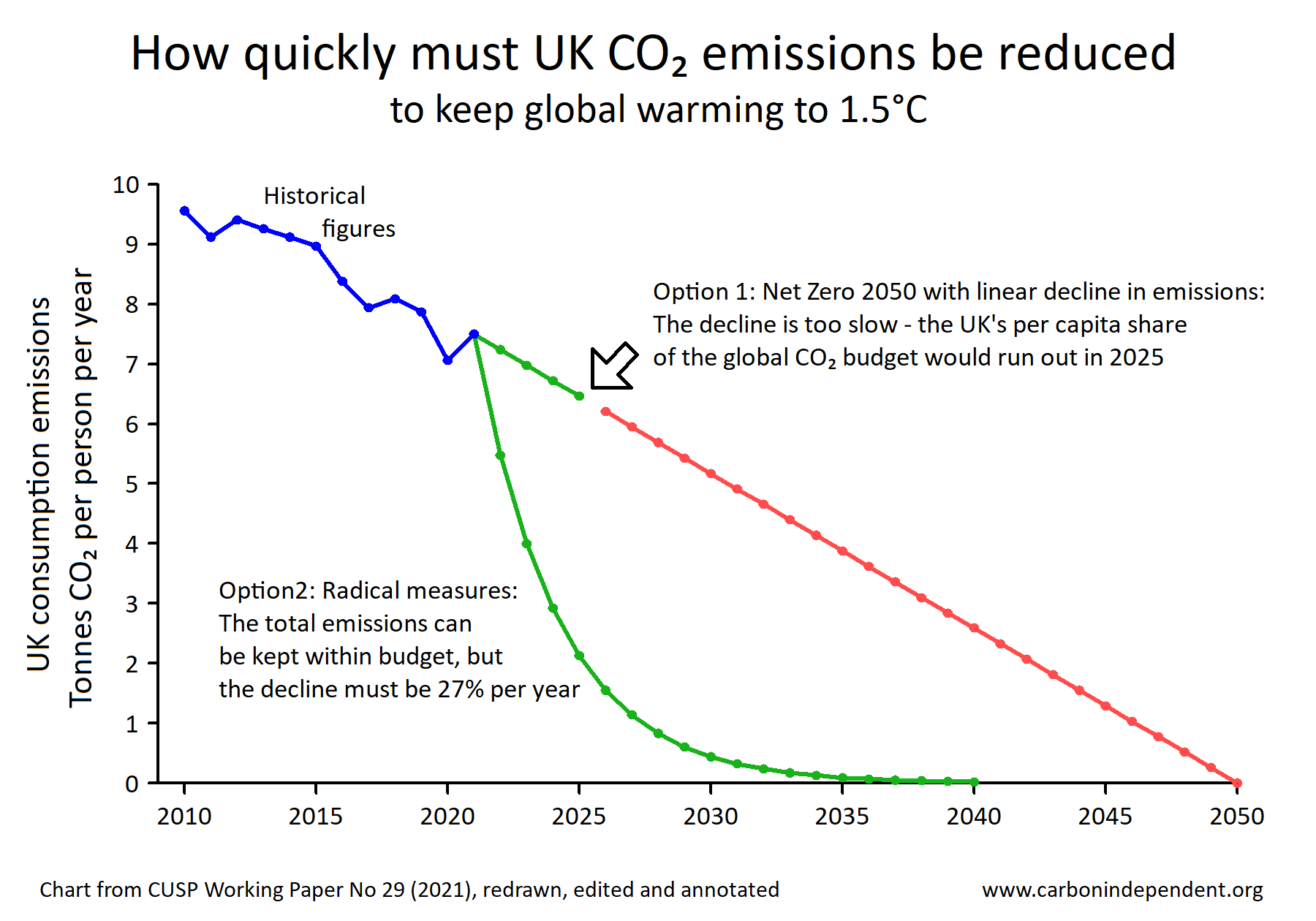

With the UK's per capita "fair share" CO2 budget running out at the end of 2024 at the current emission rate, radical emission cuts of over 25% per year are needed in order to comply with the UK's commitments to a limit of 1.5°C, as shown in the analysis from CUSP at Surrey University [5]:

See also document 162.

See also document 162.

Do any policies discussed comply with this timescale for urgent radical cuts in emissions?

including avoiding

- Net zero dates - e.g. the UK Government's Net Zero 2050 timescale does not meet the UK's Paris Agreement commitments - it would take three times the UK's per capita "fair share" of the global CO2 budget for 1.5°C - see document 109

- Electric vehicles

- Tree-planting

- Offsetting

- "Hydrogen power"

Potential applications

The checklist could be used- by authors wanting to write accurate articles in line with the science

- in assessing media articles, campaigning reports, policy suggestions etc.

The points in the checklist should be included whenever relevant to the content of the article etc, i.e. not necessarily in every text.

1. Does climate action override other priorities?

Governments sign many agreements and make many pledges, so it needs to be made clear that climate change transcends other priorities.Pledges on climate change deserve the highest priority, because they concern not just the citizens of countries producing greenhouse gases, but affect the whole world, with wide differences between how much people are affected. Crucially, it is the people who are suffering the most from climate change who are the ones least responsible for it. It is a question of citizens in one country affecting the human rights of those elsewhere. The fossil fuels already burnt are causing a gross injustice, and continuing to burn fossil fuels adds to that injustice. Meeting climate commitments should therefore be made the highest priority, and policies on climate change should reflect this high priority.

A checklist rather than a scoring system

An alternative to a checklist is a scoring system covering the same points - and a scoring system was piloted by the author in a study of UK government climate scientists - see document 133. A checklist seems preferable for the following reasons.- a checklist is more flexible, and so has a wider ranger of applications

- in many circumstances, a score of 90% is excellent, but it is generally not acceptable in documents in science or medicine: if a scientific paper has just one major flaw, it should not be published until that flaw is corrected, and if just one major injury is mishandled in a patient with multiple injuries, the patient's survival is put in jeopardy. The climate emergency requires attention to detail, and 90% perfect is not good enough.

- a checklist avoids the problem of how to score inapplicable items - whether they should be given the minimum or the maximum score

- a checklist feels less confrontational, something that is of assistance rather than something being used as a weapon.

References

| [1] | Iain Walker and Zoe Leviston (2019) There are three types of climate change denier - and most of us are at least one The Conversation https://theconversation.com/there-are-three-types-of-climate-change-denier-and-most-of-us-are-at-least-one-124574 |

| [2] | Turning delusion into climate action - Prof Kevin Anderson, an interview (2020) Responsible Science https://www.sgr.org.uk/resources/turning-delusion-climate-action-prof-kevin-anderson-interview |

| [3] | Scientists for Global Responsibility. A science oath for the climate: text and signing (2020) https://www.sgr.org.uk/projects/science-oath-climate-text-and-signing |

| [4] | BMJ (1996) Checklists for statisticians BMJ 1996;312:43 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.312.7022.43a |

| [5] | See the commentary at document 128; or the report: Jackson T (2021) Zero Carbon Sooner: Revised case for an early zero carbon target for the UK. CUSP Working Paper No 29. Guildford: University of Surrey. https://cusp.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/WP-29-Zero-Carbon-Sooner-update.pdf |

First published: 22 Jul 2022

Last updated: 21 Aug 2023

✖

✖